Schwarz

View current page

14 matchs for Geller:

Andrew M. Geller's Frank House reduced to $1.299M

In the Pines, In the Pines...

Andrew Geller house for sale East Hampton

Rip Andrew geller here

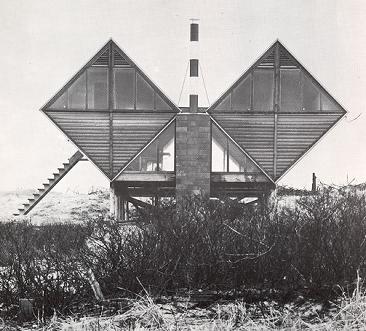

Jake Gorst, a documentary filmmaker, has moved into an 1890s Long Island home in Northport, where the architect Andrew Geller, his grandfather, spent a career playing with geometries. Mr. Geller’s most famous work is being preserved: the Pearlroth House in Westhampton Beach, N.Y., with two diamond-shaped wings often said to resemble a bra.

Mr. Gorst; his wife, Tracey; and their two daughters have preserved the attic office, down to the tobacco-smoke stains on the wood ceiling and racks of tweed jackets, protractors and T-squares. Drawings and models keep turning up in closets and crannies.

american culture between the wars kalaidjian

The avant-garde, popular, and working-class texts that Walter Kalaidjian discusses in his new work attempt to revise episodes in American culture that together constitute what he calls "a neglected cultural history" (8). Concentrating on such supposedly marginal moments in American culture as the Russian Revolution, the Harlem renaissance, the radical experimentations of the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poets, and the popular interventions of feminism, Kalaidjian dexterously blurs the boundaries between high and low culture, politics and aesthetics, and academicism and popular forms. Kalaidjian's book is divided into five chapters, each of which is, in turn, nicely divided into subsections dealing with a more specific aspect of the theme that the chapter treats. The first chapter, entitled "Revisionary Modernism," discusses the role of transnationalism during the interwar years as a key episode in the shaping of American culture. Within the chapter, Kalaidjian pays particular attention to the influence of the Russian avant-gardes in the formation of a strong Marxist-socialist consciousness in America. The second chapter explores how various "subgroups," like the Chicago John Reed Club, the New Negro movement, and the politicized aesthetics of Diego Rivera, Hugo Gellert, and Louis Lozowick, among others, "signaled a communicative difference from the dominant ideological signs of American commodity culture" (61). The section on Diego Rivera is perhaps the best part of the whole book. Chapters 3 and 4 discuss feminist concerns and radical movements in poetry respectively. Kalaidjian places these two important contemporary movements vis-a-vis the economic, political, and social concerns that he claims inform these movements. The work of authors who tend to reclaim the mode of "cultural critique," whose political edge, Kalaidjian claims, "cuts through the semiosis of everyday life and goes to the heart of postmodern spectacle," is the concern of chapter 5. This chapter criticizes the postmodern emphasis on the disappearance of the "real" (263).

Kalaidjian's purpose is not, however, simply to subvert the traditional, learned critical paradigm. His text shows that in High Modernism, Eliot, Pound, and Stevens, for instance, cohabited with the Dynamo group of poets. Kalaidjian's conflation of such apparently dissimilar poetic modes is not aimed at privileging one over the other. He argues, correctly I believe, that a thorough understanding of the period should take into account both discourses, since frequently the existence of one can throw light onto the other. One commonplace of High Modernist criticism, for instance, is to focus on the ahistorical stance most of the canonical poets adopted. By centering their discursive practices on transcendental concerns, poets like Eliot and Stevens ignored the urgent economic conditions affecting the country. This kind of anti-High Modernist discourse proves futile because it does not move further from the figures it supposedly attacks. Anti-Eliot discourse is, as it were, still focused on Eliot. Kalaidjian pushes beyond this sterile and circular critical move and cleverly shows, for example, how Ben Matt recasts Hart Crane's mythic bridge into a more politicized language to accommodate The Bridge to the discourse of political criticism. Kalaidjian argues that this kind of poetry arose from the period's deep dissatisfaction with American culture's emphasis on an increasingly automated labor process. Thus the critical veneration of such ahistorical writers as Eliot and Pound parallels the fate of society where workers "found themselves increasingly alienated from ever more automated systems of production, engineered and administered by a new class of technological experts" (154). Sol Funaroff, similarly, in "What the Thunder Said: A Fire Sermon," rearticulates Eliot's transcendental and historically unspecific resolution of social disillusion by turning it into a "materialistic vision of international class revolt, linking the unrest of pre-revolutionary Russia to depression era America" (154). Kalaidjian's work thus uncovers a historical and cultural layer that the predominant critical mode in United States, with its emphasis on individual genius, as it were, has buried in forgetfulness. His work therefore forces the reader to understand that the work of literature is, whether we like it or want to admit it, always inescapably part of a social field.

The Stamford store is one of 12 Lord & Taylors designed by Andrew Geller, Loewy's in-house architect. Geller's grandson, Jake Gorst, met with the president of National Realty & Development Corp., John Orrico, in October, but failed to convince him to preserve the building. Orrico's letter to the state Historic Preservation Officer last summer said, "There is a small group that is opposing this project, and I believe that, in their effort to try to block us, they are using [the state historic preservation] office as a pawn."

The architect Andrew Geller gazed up at the beach house's soaring glass windows, the walls that angle inward, the catwalk jutting toward the ocean, and marveled.

"I'll be damned, it's still here," he says.

Geller, now 83, had gained fame in the '50s and '60s for small and startling modern beach houses that set cubes on edge, angles atilt and conventions aside. Now, on the day after Labor Day with a sky as blue and bright as anyone visiting a beach house could wish for, he had come to visit this house built on a high sandy hill in the Pines on Fire Island in 1961. Known as the Frank House, it had just undergone a three-year renovation by its current owner, Philip Monaghan, 52, working with architect Rodman Paul, who restored it to its original form.

This Saturday night, you could win a classic mid-century modern Herman Miller chair and at the same time help raise funds to save from demolition a classic mid-century modern beach house by Long Island architect Andrew Michael Geller.my previous postings on the pearlroth house. thanks to google news alert i received this short notice cry for help. i cant believe the pearlroth estate (always with the threat of immediately pending demolition!), please read on, its a horror story. save the

Design Within Reach Studio at 30 Park Place in East Hampton will host a silent auction and raffles from 7 to 9 p.m. to raise the money needed to move the acclaimed Pearlroth House from 615 Dune Rd. in Westhampton Beach to public land five miles farther east on Triton Beach. Built in 1959, its double-diamond shape has been compared to a box kite and a square brassiere, and is widely acclaimed by architects, critics and historians as an influential example of the Hamptons' innovative and witty - and fast disappearing - post-World War II beach house architecture.

The heirs to the Pearlroth House will demolish it unless it can be moved before the spring building season. Current regulations would make it impossible to renovate it as a dwelling without substantially changing it, and its owner offered to donate the 600-square-foot house to the architect's grandson, filmmaker and historian Jake Gorst. He and fellow preservationists say they'll need about $200,000 to relocate and restore the structure, which they hope will house a museum of mid-century architecture at its new site.

For more information about the Saturday fundraiser, which will feature a slide presentation, wine and cheese, as well as the silent auction - and to learn how to make a donation - call Gorst at 631-651-9939.

a m geller's grandson jake gorst's email to curbed regarding pearlroth house:

We've managed to raise enough money to move the house, but the Town of Southampton now requires that we put $25,000 in a passbook savings account so they can access it in the unlikely event that we abandon the restoration project before February 2007. Essentially they want us to pay to have it torn down if we "give up" - which is not in our vocabulary.

By BRUCE LAMBERT

Published: May 6, 2005 for NYT

As soon as it was built in 1959, the beach house at 615 Dune Road in Westhampton Beach caused passers-by to stop in their tracks.

"The house stood out like a spaceship that landed on Dune Road, so it was quite an attraction," said Jonathan S. Pearlroth, who inherited the house.

Its unusual "double-diamond" geometric design, with two adjoining rectangular boxes tilted on their edges, quickly became an icon of modernism and was featured in magazines and books.

But the Pearlroth family eventually reached the reluctant conclusion that the double diamonds would have to go. It needed more room, Mr. Pearlroth said; old additions needed replacing and new laws barred expanding the original structure because it is in a storm damage zone. So the family hired an architect to design a larger replacement house and is ready to clear the site as early as May 15.

Hoping to rescue the house, preservationists are campaigning to move it to a new site, restore the original condition and transform it into an architecture museum.

"We're racing against the clock, trying to get the funding just to do the move," said Jake G. Gorst, the grandson of the house's architect, Andrew M. Geller.

Over the decades, the house had gradually faded from sight. Despite the beachfront locale, wind and waves built up the dunes so much that the house lost its prominence and even its ocean view. "It was buried," Mr. Pearlroth said.

Neighboring houses sprouted, and it was further hidden when the Pearlroth family expanded its living space by building decks and bedrooms around the original structure, which is just 600 square feet.

If preservationists succeed in salvaging the house, they can thank a series of lucky breaks.

Mr. Gorst, a filmmaker who was working on a documentary about his grandfather, interviewed Mr. Pearlroth in February. It was then that the owner sadly explained his demolition plans.

"We have such sentimental ties to the house - I loved it - it was painful for us to think we would knock it down," Mr. Pearlroth said this week.

The plan caught Mr. Gorst by surprise. But as they talked, a new idea suddenly dawned on Mr. Pearlroth.

"It was like a light went off in my brain," Mr. Pearlroth. "I said, 'Jake, please take the house if you can save it and do something with - it's yours.' "

Mr. Gorst leapt at the challenge, becoming part of the story he was filming. He spoke to Exhibitions International, a nonprofit group in Manhattan promoting 20th-century architecture, which agreed to raise money. Organizers figure they need $50,000 to move the house and $150,000 for restoration.

"It's coming in dribs and drabs so far," said the group's director, David L. Shearer. "We have a long way to go. The problem is the house is not 100 or 200 years old. People don't always appreciate the historic significance and need to preserve modern architecture."

The first hurdle is raising various utility cables so that the house can be slipped underneath. Cablevision has agreed to charge no fee, the organizers said, and they are in talks with the Long Island Power Authority and Verizon about their lines.

If the house can be moved, the next issue is where to put it - especially since vacant waterfront property in the Hamptons is almost as scarce as double-diamond houses and commands princely sums.

Once again, fate is intervening. As word of the fledgling campaign spread, an advocate in the American Institute of Architects, Anne R. Surchin of Sag Harbor, took up the cause.

"All the modern houses are being torn down left and right, and some are real classics," she said in an interview. "Sometimes you don't find out they're in danger till you see the bulldozers."

Linda A. Kabot, a member of the Southampton Town Council, said that after Ms. Surchin "sent me a frantic e-mail" she conferred with a fellow Council member, Steve Kenny. He suggested offering a site on the bay side of Pikes Beach park, a mile down the road.

Next Tuesday, the Town Board will hold a hearing on that proposal. The sponsors expect approval that day, to beat the move-it-or-lose-it deadline.

In one of many endorsements for the hearing, an architecture historian, Alastair Gordon, praised the house as "one of the most important examples of experimental design built during the postwar period not just on Long Island but anywhere in the United States." He called it "witty, bold and inventive."

With the proposed site surrounded by open space and the house to be elevated on stilts to prevent damage from stormy seas, the setting would recreate the original look of 1959, proponents say.

"It could be a wonderful architectural and navigators' landmark," Mr. Kenny said. "Perched high, almost like a work of art on a pedestal, the view looking out over the bay is going to be spectacular."

Mr. Geller, whose résumé includes work on the Lever Building interior, Windows on the World and Lord & Taylor's logo, recalled the Pearlroth house as "a one-of-a-kind" project that he did for fun.

Mr. Pearlroth's mother, Mitch, recruited the architect after reading about another house he designed. Mr. Geller said he studied the site and the family's living habits "previous to any doodling on paper."

Because the Pearlroths lived in New York City, Mr. Geller designed their beach house "to escape from the cell-like appearance of an apartment, to stay clear of four walls." The high-peaked ceilings also invoked the feel of an American Indian tent, he said.

The whimsical house inspired nicknames to match, including the Square Bra, the Box Kite, the Cat, the Milk Carton and the Reclining Picasso.

At 81, Mr. Geller said he was grateful for the effort to save the house. "I'm flattered," he said, "and I'm just thrilled."

jonathan s pearlroth sounds like a total load :

"It was like a light went off in my brain," Mr. Pearlroth. "I said, 'Jake, please take the house if you can save it and do something with - it's yours.' "a light just went of in my brain, let (inheritance-boy) pearlroth pay to move it. creep!

ps: would it kill the nyt and curbed to point out what a sleezy move this is?

andrew michael geller

from countercube : architectural art / the beach houses of andrew geller

"This innovative multimedia project consists of a feature length documentary, an interactive web site and a series of lectures to be held throughout the North East. Funding for this project is made possible from tax-deductible donations from individuals, corporations and foundations with an interest in the betterment of the arts. This website will feature the complete production schedule, information pertaining to Andrew Geller and the film and information on upcoming speaking events."

More on the most important Andrew M. Geller and the Leisurama home.