Ink Jet

Matt Chansky, Claire Corey, Tom Moody

Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, CT

September 24, 2000 - January 7, 2001

Essay by Richard Klein, exhibition curator:Revolutions often start in curious ways. Throughout the history of art, change is set in motion by factors such as political or social upheaval, new philosophical constructs, scientific revolutions, or the basic human urge towards novelty. For artists Matt Chansky, Claire Corey, and Tom Moody, however, opportunity presented itself through the reality of day jobs in today's high-tech office environment--using graphic design and illustration computer programs, photocopy machines, and digital ink jet printers. Originally trained as painters, each of these artists has made the transition into the digital realm through experiences in the workplace. Rather than simply scanning and manipulating images, Chansky, Corey, and Moody have each struggled in their own way to completely reinvent painting inside the computer.

Matt Chansky's edgy text-based works at first glance seem to recall the classic modernist abstraction of painters such as Mark Rothko or Barnett Newman. These images, however, have evolved out of the underlying fabric of all digital imaging: computer programming. The artist "collects" error-messages, the coded information that communicates program malfunctions, layering them to form dense fields of color and texture, creating a hypnotic, trance-like effect. A final layer is added consisting of dialogue between "John" and "Jane," the artist's virtual Adam and Eve, who pose questions to each other in the abbreviated freehand characteristic of email. Fusing the poetic and philosophical with the catchy insidiousness of advertising copy, these characters seem to struggle with their digital existence. Fifty years ago, Abstract Expressionism explored both the tragic and the sublime through a painterly engagement with space and color. Chansky's work updates this expressionistic tradition by presenting information, in addition to classic, formal concerns, as part of the cultural baggage that makes up the current human condition. Going beyond the beautiful surface of Chansky's abstractions, the layered text reveals fragmented, plaintive meditations on identity, loss, and memory.

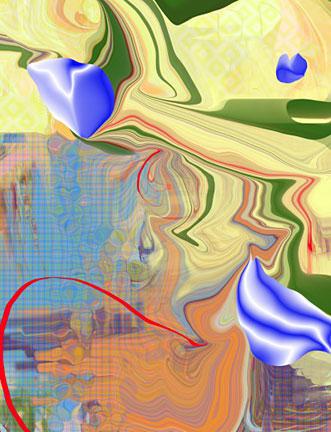

Claire Corey's computer background grew out of her experience as a publication production manager in the museum world. Initially working with Adobe Illustrator and Photoshop, Corey became fascinated with the glitches and errors that occurred when printing out projects. The more facile she became with the programs, the more she realized that she could achieve effects that the programmers who created such software either had not considered, or had relegated to the realm of improper procedures. Slowly leaving traditional painting materials behind, Corey retrained herself to paint using these programs. Similarly to Chansky's, Corey's paintings superficially reference Abstract Expressionism--in her case, the fluid paint handling of Willem de Kooning or Helen Frankenthaler. On closer examination, however, these works have a strange, almost surreal presence, combining turbulent fluid dynamics with a saturated psychedelic color sensibility. Corey's works often have a vortical composition--drawing the viewer in with details to reveal complex paintings-within-paintings that are only possible due to the image's digital origin. As abstract artists at mid-century tried to to become nature, not simply illustrate it, Corey's current process has enabled her to merge her sensibility with the electronic nature inside the microprocessor, revealing a reality as strange as NASA's recent digital images of Jupiter's atmosphere.

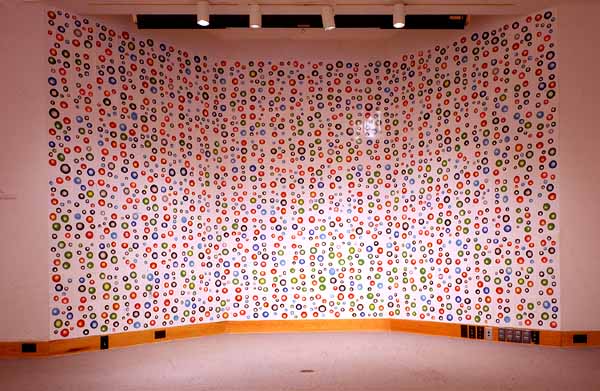

Classic concerns of what constitutes beauty, coupled with the ongoing dialogue between abstraction and representation, fuel Tom Moody's PC-based works. Rejecting sophisticated, high-powered programs and expensive hardware, Moody utilizes simple paint and drawing programs as an antidote to the slick overproduction that categorizes much contemporary visual culture. More minimal than the work of Chansky or Corey, Moody's art harkens back to the moment in the late 1950s when overall, color-field painting, as championed by Clement Greenberg, competed with the first stirrings of Pop art. The artist's "ball" abstractions are akin to Pop in their deadpan presentation of office-paper-pinned-to-the-wall, yet are as spatially mesmerizing as the tangled skeins of enamel in Jackson Pollock's paintings. Moody's "Polygamy" series started as a series of quick sketches the artist drew at work. Looking at the plastic images of women's faces used in print advertising, Moody renders them freehand using the Paintbrush program. After the image has been completed, the artist then "selects" individual features, such as the nose or eyes, and moves them around until he feels the face is perfect. Not meant to be a specific likeness of an individual, Moody sees these images ultimately as an exploration of the superficial and formal qualities of ideal beauty, acting as a foil to his more purely abstract works.

Each of these artists has stopped making paintings by traditional means. The question then arises, can the works produced by Chansky, Corey, and Moody be considered paintings? The answer might lie in the issues raised by photography's ongoing impact on painting: in response to the unquestionable veracity of the photographic image, paintings ceased to be revered as representational "windows" onto the visible world and instead were considered primarily as literal things, objects with paint on their surfaces. For artists taking painting into the computer, the most profound results are neither illusions nor objects, but information-laden surfaces that contain the mutability and complexity of information itself. The works in this exhibition are perhaps not paintings, nor are they prints or drawings. They are, however, certainly informed by the historical continuity of painting. As computers become ingrained in all aspects of cultural production, the net effect is the breaking down of categorization, the blurring of the boundaries between one type of image making technique and another. If indeed the "medium is the message," then the new hybrid works, such as those in this exhibition, are a radical break with the past. As the title of Matt Chansky's "Digital Eden" series implies, this is a beginning, the first giddy steps into a garden whose size and shape remains unknown.

Photos, top to bottom: Tom Moody, Sphere-o-rama, 2000; ink, paper, map pins, 260 sheets of 11 x 8 1/2 inch paper, installed dimensions 104 1/2 x 203 inches (click on image for larger version shot in different light); Matt Chansky, Digital Eden, No.5, 2000, ink on paper, 50 x 34; Tom Moody, La Femme Nikita (realistic version), 2000, ink on vinyl, 42 x 60 inches (installation view); Claire Corey, Untitled Painting #1e2l, 2000, ink on watercolor paper (iris), 60" x 46".