View current page

...more recent posts

Church of Lo Fi

A friend just jokingly referred to my preference for old computer programs over current software as my "religion." No, religion is believing you have to buy the newest program to make the best art. The opposite of that is...iconoclasm?

But idol-smashing can be dogmatic, too, so maybe it's better to couch the discussion in terms of "desired artistic effects." My old dying Mac SE makes cool sounds from the clipping and distortion that comes from "overdriving" the machine's limited synths, just in normal use--rhythmic patterns of clicks, ominous atmospheric rumbles... You won't get that with garageband (or maybe there's a pallette called "old Mac flaws"? I don't really want to hear about it). Also, there's something about working against limitations, as opposed to having a machine that "does it all for you." Think movie special effects on a budget vs profligate CGI. And finally, there's a certain exoticism of hearing/seeing old tools as they were before years of "improvements." Some of those improvements are engineering tweaks (for speed, etc) but others are simple value judgments the user had no input in. As Dan Graham once said--in so many words, and not necessarily for this reason--the "recently outmoded" can be one of the more fertile and radical places for artists to work.

Anyway, if lo fi is a religion, here's a chapter of the Bible, written by painter Alexander Ross for the "Static" show co-organized by John Pomara and me in '98 (I especially like the bolded para.):

The Recent History of Static in Recorded Music

by Alexander Ross

The static trend in rock music grew initially out of the fuzz guitar sound (best known from the Rolling Stones' "[I Can't Get No] Satisfaction"), which imitated an over-driven or distorting amplifier. Hard-rock outfits continued to push the "guitar wall of sound" well after the '60s, refining it into a subtle and controlled art.

The creative fringe took interest in an accidental by-product of this distortion: the overtones of fuzz, a warm "pink noise" (white noise is static without tone, pink noise is static or "snow" with a hum, or discernible pitch) that rode seemingly independently on top of the music. An early exploration of this might be Eno's "Needle in the Camel's Eye" from 1973, where the constant smashing of guitar chords creates a wall of wavering noise above the song.

A foundational work appeared in the mid-'70s with Lou Reed's controversial and fan-disappointing double LP Metal Machine Music, an all-static-and-feedback statement that figures in rock history much the way Futurist noise performances function in the history of theatre: pure, unequivocal rebellion.

There were some notable static undergrounds coming along in the late '70s/early 80's, namely Chrome (out of San Francisco), and a little later Fi (pronounced "eff eye"). Throbbing Gristle might also be mentioned here, as well as This Heat and Cabaret Voltaire (for example, "No Escape" off their classic first release, Mix-Up). The first group to make the intentional breakthrough into pure static would have to be The Jesus & Mary Chain, who eq-ed the bass-end off the fuzz chords entirely, leaving a shrill, static constant running relentlessly throughout their songs. Next would be Kevin Shields of My Bloody Valentine, where the static becomes more textured and smeared, literally permeating the music. The effect is a sexy, dreamlike blur echoing early '90s trends in fashion photography. Static finally becomes the main subject with the rise of Flying Saucer Attack (Chorus is a good example), out of Virginia, of all places. Here the static is totally frontal, and the music sort of whispers at you through a snowy haze.

The advent of the compact disc in all its sterile flawlessness brought about the realization that technological defects such as tape hiss, amp buzz, record groove ticks, and ultimately the computerized glitches sometimes heard on the CD itself were now interesting sounds never before utilized in conjunction with music. This, combined with the inexpensive home recording boom, coalesced into what became known as LO-FI. Major players, largely confined to the US and New Zealand, include Lou Barlow/Sentridoh, Daniel Johnston, Guided By Voices, and (from New Zealand) post-rockers The Dead C and This Kind of Punishment.

Mid-'90s developments quickly cross-over into the techno-ambient realms with Oval, who boldly dominate the glitch and hiss scene. Mention should be made of Scanner, an individual who scans cell phone conversations and create pieces out of them, with the natural static of the transmission wavering in and out. Most recently is Porter Ricks, also techno-ambient, whose distant discotheque is heard pleasantly through walls of dreamy smush.

The ambient/industrial sector was long-ago onto the static phenomenon, but here there is no music at all, just pure, wonderful noise. Examples here would be The Hafler Trio, Arcane Device, Tibetan Red, PBK, and early Nocturnal Emissions.

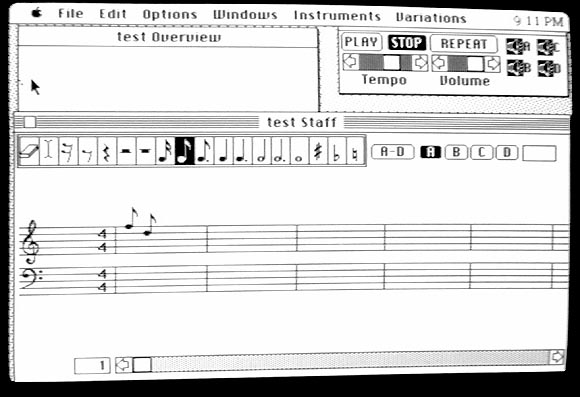

MusicWorks for Macintosh was one of the first music software programs for home consumption (ca 1984); it takes up a whopping 69K of memory. I still use it: it acts as a primitive sequencer, letting me cut and paste loops that I write into some kind of coherent (hopefully catchy) song or composition. It gets a nice, unsophisticated video game sound, with about 10 "instruments"--e.g., piano, organ, trumpet (uggh), chime, synth 1, synth 2--and controls for the attack and decay as well as tremolo and vibrato. The pieces I did in '88, when the computer was relatively new, are more structured (i.e. songlike) than the most recent stuff, which is more "tracklike" and features found sound (other folks' lock grooves from turntables, etc.). A new composition will be posted soon, something I'm pretty happy with--a score for another artist's video--that's more in the '88 spirit.

Unfortunately the ancient Mac SE I run MusicWorks on seems to be dying; it takes longer and longer to save and I've lost some work. I like this little music program a lot--it's sort of the aural equivalent of MSPaintbrush, which I'm also fixated on--and I'm hoping it can be run on the newer Macs. If it can I'll plunk down and buy one.

My Complete Musical Works in MP3 Form

1998 - present

1. Scratch Ambulance [3.7 MB]

2. Phil's Revenge (TM vs Ectomorph) [2.1 MB] / hi-fi [2.6 MB]

3. Brakin' 1 [1.8 MB]

4. Brakin' 2 [2 MB]

5. Calypsum (TM vs M. Mayer) [3.3 MB]

6. Migrant Song [2.3 MB]

7. Streetsong (TM vs 8BCS) [2.84MB]

8. Eins Zwei Drei (Melody) [mp3 removed]

9. Monster Scales [1 MB]

11. Robot Landscape [3.6 MB]

1988

1. Arpeggiasm [2.6 MB]

2. Dance of the Nematodes [3.3 MB]

3. Lament for a Treefrog [1.8 MB]

4. Life in the Mortuary [1.1 MB]

5. Pass the Amphetamines [1.5 MB]

6. Spring Has Sprang [1.2 MB]

7. The Organist Died [.9 MB]

Ralf Hutter of Kraftwerk. The second most influential pop group after the Beatles is touring in support of Tour de France Soundtracks, their first CD of new material in 18 years. While not as aggressive, funky, or strange as their earlier work, it's good: kind of shimmery and ambient and yes, they can still write hooks. "Vitamin," "La Forme" and the remixed 80s hiphop classic "Tour De France" are quite hummable. They sound as if they spent all those years tracking down every trace of hiss and hum in their studio and then carefully mastered every millisecond because it's an amazingly clean, refined production. One thing they still have over the generation of electronic dance musicians they inspired is great technical finesse, and I'm guessing machines expensive enough to produce sounds and textures beyond the budgets of most basement producers. They don't flaunt it, though; the music is very understated. More tour photos in addition to the ones above, by Swedish photographer Henrik Larrson, are here. A review of the Brixton Academy show is here. See comments to this post on my main weblog page. |

cuechamp recently posted a music mix titled "source code" [dead link], consisting of the original songs--mostly from the '70s--that were subsequently, heavily mined for sampled drum breaks by hiphop and drum & bass producers. If you've listened to any music other than country (and maybe even that) for the last 25 years you will also recognize many of the piano stabs, vocal hooks, and random cowbells in these R&B, funk, and fusion classics (they were also very popular with house and garage producers). cuechamp doesn't layer or mash up the tunes: one song respectfully follows another in a nice flow that would also make it an excellent house party soundtrack. Here's the tracklist:

1. chase the devil - max romeo and the upsetters

2. amen, brother - the winstons

3. think about it - lyn collins

4. apache - incredible bongo band

5. ready or not - the delfonics

6. take me to the mardi gras - bob james

7. i'm gonna love you just a little more - barry white

8. shack up - banbarra

9. you can't hide from yourself - teddy pendergrass

10. scorpio - dennis coffey

11. fate - chaka khan

12. dance to the drummer's beat - herman kelly (I love this one -tm)

13. all this love that i'm giving - gwen mccrae

14. get out of my life woman - lee dorsey

15. far beyond - locksmith

16. ashley's roachclip - soulsearchers

17. i love you more - george duke

18. champ - the mohawks

19. praise you - camille yarbrough

20. funky drummer - james brown

It would be interesting to create graphs showing all the subsequent uses of sound bites from this "source code." If you sorted them by length you'd probably find the samples get longer in proportion to (1) the age of the track using the sample and/or (2) the economic strength of the samplee. This is because of an "invisible attractor" force in current creative endeavors called The Law. Early house and hiphop was made in the day before humorless poor sports like The Turtles started suing and winning cases for their precious string snippets. Nowadays the samplee becomes an involuntary creative partner in the new production, depending on the amount of lawyer fees he/she can afford (or recoup on contingency). Such issues are discussed in Lawrence Lessig's new freeware book, also linked to on cuechamp's page.

Here's a relevant quote pulled not from Lessig's .PDF but from a NY Times article about the Danger Mouse Grey Tuesday protest, before the article disappeared into the Times' proprietary vault:

Jonathan Zittrain, a director of the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard Law School, said the issue is indeed a gray one. "As a matter of pure legal doctrine, the...protest is breaking the law, end of story," Mr. Zittrain said. "But copyright law was written with a particular form of industry in mind. The flourishing of information technology gives amateurs and home-recording artists powerful tools to build and share interesting, transformative, and socially valuable art drawn from pieces of popular culture. There's no place to plug such an important cultural sea change into the current legal regime." (emphasis added)