Schwarz

View current page

...more recent posts

A girl and a gun? An appreciation of Hollis Frampton's cinema begins with the admission that a film requires something far simpler than Jean-Luc Godard's basic recipe. Frampton, who died in 1984 at age 48, thought the perfect film would project a rectangle of white light. "But we have decided that we want to see less than this," says Frampton's narrator in his statement of principles/performance piece A Lecture. "Very well."

Frampton may have decided it was foolish (and, on a basic cognitive level, impossible) to deny audiences the familiar and expected pleasure of narrative--none of his films resemble that Platonic ideal of white light. (nostalgia), his best-known film and a clear masterpiece, presents a familiar autobiographical scheme, as the narrator reminisces over a series of thirteen photographs. But the presentation is dissonant, and the viewer is only gradually taught how to watch the film. The photographs disintegrate into ashes on a hot plate, beginning with "the first photograph I ever made with the direct intention of making art" and ending with something that makes him believe "I shall never dare to make another photograph again." So explains the narrator, who in the first deliberate act of misdirection is not Frampton but his friend the Canadian filmmaker Michael Snow. (The voiceover gets exceedingly nested when Snow, narrating for Frampton, refers to Snow, saying with resignation, "I wish I could apologize to him.") He perpetually refers to the forthcoming photograph rather than the one smoldering before the viewer's eyes, creating a disjunction between sound and image. As soon as a new image appears, we are trying to reconcile it with the previous vignette while simultaneously listening to the narrator's recollections and regrets. In other words, we can't help but experience nostalgia. The result is alienating but rarely frustrating. (nostalgia) is a poignant depiction of the elusive nature of memory, even in an age of mechanical reproduction, as well as a deadpan prank. The critic Michael Joshua Rowin has referred to the film's final sequence--which hints at a terrifying mystery in the next photograph, one we will never see--as a three-minute retelling of Michelangelo Antonioni's Blow-Up.

not too much web documentation of national lampoons foto funnies. the series usualy involved a nude woman dropped in to some mans world situation. the format was a photographic interpretation of comic strip (funny paper or funnies) story frames. by this time in the early 70's underground comix and doonsberry * had helped re established an adult interest in the serial frame comics reading format. i offer this posting in connection to sally mccays recent academic style essay on GIF art. in connection to GIF etymology in general and specifically LM's mention [ "I find viewing films frame by frame much more formally interesting than looking at the perfect illusion of motion that they result in." ] of her GIFs distance from animated cinematic smoothness. rather a jumpy connected rhythm of readable narrative. a sort of splitting the difference between unique ideas established per (comic strip) frame and the cinematic

ease in viewing of a full rate of fps ** film experience.

* there were many soap opera / adult interest type series runing in daily news papers ie steve canyon and apartment 3-d.

** muybridge

the cavemen on gimmick rock

the umbrella house sarasota fla

ree

tv cello (1984) "can we get paris?" "yes."

portsmouth sinfonia hall of the mountain king

chris burden beam drop

the paper dress

yellow pages and campbells soup

whaledreamers

Lee Lozano isn't exactly a household name--even in art houses. But in the 1960s and early '70s, she was very much part of New York's art scene; she knew everyone and is remembered as an intense and engaging figure (her inamorati included such diversely talented men as Dan Graham and Joey Ramone). To say the least, Lozano had a strange--and brief--career; though lasting just over a decade, it encompassed a series of distinct styles and practices. For several years, she exhibited regularly, including group shows at Richard Bellamy's Green Gallery in 1964 and 1965. Later she distanced herself from the art world before finally dropping out altogether.

self-kleptomania

flip book animation fps

value theory

the americans

Mountain Retreat in Queenstown / New Zealand by Fearon Hay Architects

justin found this and its stunning

(from the collection of) olivier mossett "Portrait de l'artiste en motocycliste" October 11th at the Centre National d'Art Contemporain de Grenoble

(pdf) press release with dialog between bob nickas and olivier. (highly recommended reading for enthusiasts of one-color paintings and found object art.)

nyt maine cabin construction diary

people of walmart

via adman

the wtc a building project like no other

via things and reference library

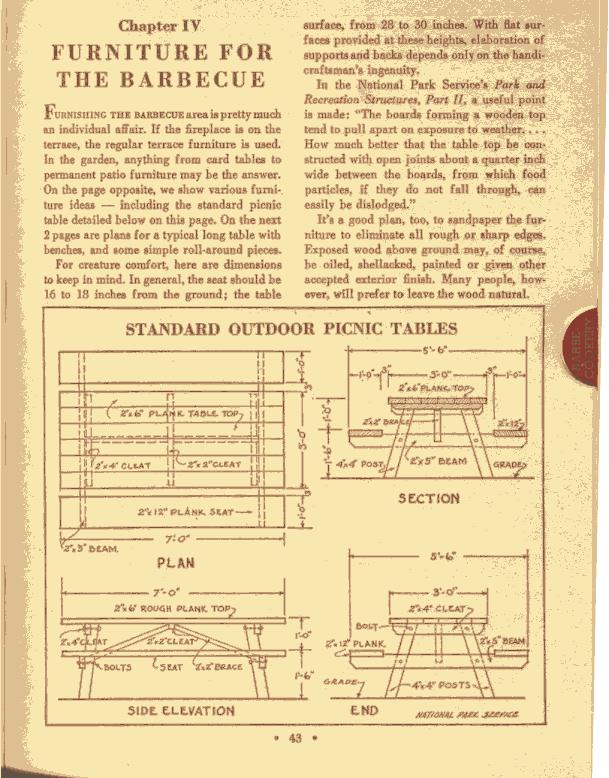

norms picnic table plans

big slabs

house dijk

Nonetheless, it was nearly impossible, while sitting in the dark watching it all unfold, not to think that it wasn't just Julius Shulman who was being eulogized and laid symbolically to rest. It was also a certain attitude about what Los Angeles means, here and abroad, and how photographers and architects alike ought to frame life in the city.

After all, in the years before his death Shulman was the greatest living symbol of the idea that Los Angeles and its architecture were synonymous with both expansion and innovation. In that sense, the memorial was another bit of evidence that L.A. is getting a little worse at crafting the future -- as icons of invention like Shulman pass into history -- and a little better at talking about and understanding itself. We are slowly trading initiative for perspective, which is perhaps the fate of any big city as it settles into middle age.

Nearly every speaker touched on Shulman's innate and irrepressible optimism, which was a fundamental element not just of his personality but also of his work. His famous black-and-white photographs of designs by Richard Neutra, Pierre Koenig, Gregory Ain and many others were not just, as Hines noted, marked by clarity and high contrast. They were also carried aloft by a certain airiness of spirit, a lively confidence that announced that Los Angeles was the place where architecture was being sharpened and throwing off sparks from its daily contact with the cutting edge.

Indeed, Shulman's great success was due in part to the fact that he came of age in a period when there was no barrier between the idea of promoting Los Angeles and of uncompromised architectural creativity. Usually these two notions are locked in at least a symbolic struggle: The businessman is the enemy of the artist, and where profit and growth take root they unavoidably crowd out the flowering of authentic creativity.

Certainly, by the 1970s, many of our most talented architects had begun to adopt that attitude, designing buildings that aimed to subvert mass culture or crass profiteering or at least reflect the tensions and inequities in contemporary society. Shulman's Los Angeles -- particularly the quickly expanding city he documented in the 1940s, '50s, and '60s when he was in his prime -- was by contrast a place where business directly fueled artistic and architectural creativity and vice versa, often without guilt or any sense of contradiction.

Shulman saw himself as a working photographer first, a booster for Los Angeles second and an artist not at all; many of Sunday's speakers, including his daughter, Judy McKee, remarked that Shulman was surprised (though also partly vindicated) near the end of his life when his work was discovered and promoted as art by gallery owners, curators, collectors and publishers.