Schwarz

View current page

...more recent posts

hillbilly multiple

gender drinking

trailer in the expanded field

totally eclipsed

*sound*warning

see marfa tx

MG truike

bowery restaurant supply

chefs catalog

les switch bldg

Everywhere I go, no matter what I do, there is always some drunk lady screaming, ‘Aflac!’

Hitler's chief architect, Albert Speer, oversaw Prora's design competition, which was won by Clemens Klotz - more on the strength of his party connections than his architectural talent. Nazi architecture tended towards either monumental classical modernism - such as Speer's famous Nuremberg grounds - or the folksy, resolutely German Heimatstil. But Prora is neither of these. Its precedents were modernism's bold experiments with the "linear city", in which all urban functions were organised into an infinitely extensible system, leaving clear landscape on either side. Ivan Leonidov proposed such a plan for the Russian mining town of Magnitogorsk, as did Le Corbusier with his Plan Obus design for Algiers. In practical terms these ideas were almost science fiction but Prora made them real. Behind the hotel block would have been a mini town of sanctioned leisure facilities: gymnasium and swimming pool; concert hall; movie theatre, and as the centrepiece, a festivity hall large enough for all 20,000 visitors. Tellingly the latter was handled by a dif ferent architect, Erich zu Putlitz, in a stripped-down classical style more in keeping with Nazi tastes.

Like his mentors, Niemeyer was a Modernist. Modernist architects strove to create disorientating environments that were self-contained and separate from their surroundings. Like the painters they associated with, they attempted to shock people into reevaluating their middle-class world view. Le Corbusier, one of the founders of the movement, tried to achieve this effect through the creation of what he called "Radiant Cities," made up of homogeneous concrete slab buildings which sat on columns, surrounded by parkland and ribboned with superhighways. Architects around the world incorporated modernist principles into their projects for the next several decades, but no one was able to build an entire radiant city. Then, in 1956, the President of Brazil, Jucilino Kubitchek, announced that he was going to commission the building of a new capital in a desolate area of rolling scrubland. Urban planner Lucio Costa won the bid and Oscar Niemeyer was commissioned as the chief architect.

rip john delorean

It would be equally pointless to imagine that any architectural project could be reduced, either in analysis or design, to a definitive map that could account for all the forces at play, to a totalizing diagram of formal, psychological, and social relations. The convergence of discourses and economies at the nexus of subject, space, site, or program provides an opportunity not to resurrect an ultimate truth-value of "Site" or "Program," but to utilize each force against itself, against the other forces, and against the entire project. The nostalgia of current "contextualism" can be interrogated by architecturally utilizing past or present aspects of the context to simultaneously problematize the object by the site and the site by the object. The naive problem-solving of sixties behavorialism can be similarly interrogated by architecturally utilizing the program to question certain institutional practices. In all cases, any representation of these forces will always be one of many possible representations.

Yet if we interpret everything in terms of machines and the effects of machines, if everything flows and merges, how are we going to get a grip? Here the diagram plays a fundamental role. Deleuze borrows the concept from Michel Foucault, who employs the word in Surveiller et punir (1975) with respect to panopticism. Foucault observed that the panoptical prison had a function that went beyond that of the building itself and the penitentiary institution, exercising an influence over all of society. Stressing the function of these machines, which produced various behaviours, he discovered this coercive action in workshops, barracks, schools and hospitals, all of which are constructions whose form and function were governed by the principle of the panoptical prison. According to Foucault, the diagram 'Is a functioning, abstracted from any obstacle... or friction [and which] must be detached from any specific use'.9 The diagram is a kind of map that merges with the entire social field or, in any case, with a 'particular human multiplicity'. Deleuze thus describes the diagram as an abstract machine. 'It is defined by its informal functions and matter and in terms of form makes no distinction between content and expression, a discursive formation and a non-discursive formation. It is a machine that is almost blind and mute, even though it makes others see and speak.'10

The concept of radical immanent criticism is inspired by traditions drawn from film, literature and theatre, from the ideas of the International Situationists and from recent studies of the urban field and of social theory. It is a form of criticism that tries to unmask the representation of institutions, but without disqualifying that representation or the predominant visual culture in its own right. 'Unmasking' is not something you do in order to uncover an authentic ideal unsullied by the spectacle, but to break the representation open. The aim is to be able to see realities that are free of a simulation where nothing matters any more. Seeking the authentic is a praiseworthy starting point, but a quest for authenticity that depends on the negation of spectacle is a hopeless, naIve struggle. It is more fruitful to seek a constant unmasking of all kinds of institutional values that reside and hide in our society of the spectacle. This implies that movement, dialogue and conflict are primary. Hope lies in the permanent unmasking of alienation. After all, in everyday life there will always be alienation. And without alienation there can be no philosophy

Architecture: the Essay

via architexturez>>criticism and architecture

by Georges Bataille

Architecture is the expression of the very soul of societies, just as human physiognomy is the expression of the individuals’ souls. It is, however, particularly to the physiognomies of official personages (prelates, magistrates, admirals) that this comparison pertains. In fact it is only the ideal soul of society, that which has authority to command and prohibit, that is expressed in architectural compositions properly speaking. Thus great monuments are erected like dikes, opposing the logic and majesty of authority against all disturbing elements: it is in the form of cathedral or palace that Church or State speaks to the multitudes and imposes silence upon them. It is, in fact obvious that monuments inspire social prudence and often even real fear. The taking of the Bastille is symbolic of this state of things: it is hard to explain this crowd movement other than by the animosity of the people against the monuments that are their real master. Moreover, each time that architectural composition turns up somewhere other than in monuments, whether it is in physiognomy, costume, music, or painting, one may infer a prevailing taste for divine or human authority. The great compositions of certain painters express the desire to force the spirit into an official ideal. The disappearance of academic construction in painting is, on the contrary, the opening of the gates to expression (hence even exaltation) of psychological processes that are the most incompatible with social stability. This, to a large extent, explains the strong reactions provoked for more than half a century by the progressive transformation of painting that, up until then, was characterised by a sort of hidden architectural skeleton.

It is obvious, moreover that mathematical organisation imposed on stone is none other than the completion of an evolution of earthly forms, whose meaning is given, in the biological order, by the passage of the simian to the human form. The latter already presenting all the elements of architecture. In morphological progress men apparently represent only an intermediate stage between monkeys and great edifices. Forms have become more and more static, more and more dominant. The human order form the beginning is, just as easily, bound up with architectural order, which is no more than its development. And if one attacks architecture, whose monumental productions are at present the real masters of the world, grouping servile multitudes in their shadows, imposing admiration and astonishment, one is, as it were, attacking man. One whole earthly activity at present, doubtless the one that is most brilliant in the intellectual order, demonstrates, moreover, just such a tendency, denouncing the inadequacy of human pre-dominance: thus, strange as it may seem when concerning a creature as elegant as the human being, a way opens up—indicated by painters—in the direction of bestial monstrosity; as if there were no other possibility of escaping the architectural chain gang.

In Documents # 2, May, 1929. Paris.

Architecture's place in art history: Art or adjunct?

In a community discussion of the look of Chicago led by a working group of three faculty and three visiting journalists from the University of Chicago's Franke Institute for the Humanities, W.J.T. Mitchell observed that he and his fellow faculty tend to take the local built environment for granted, depending on newcomers to provoke them to notice its qualities. Invoking Walter Benjamin's observation in his essay of 1936 "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction," Mitchell concluded that Benjamin remains correct in claiming that we receive architecture in a state of distraction. (1) In this case, however, distraction was not working through architecture in the sense in which Benjamin imagined it working, to redemptive revolutionary effect. Here it was the contemplative reporters for Time, the New York Times, and the Chicago Tribune who had the most to say about how buildings engage problems of visual culture, while the faculty related to their own built environment in a mode of distraction unharne ssed to empowering revelation. (2)

Customers who bought this book also bought:

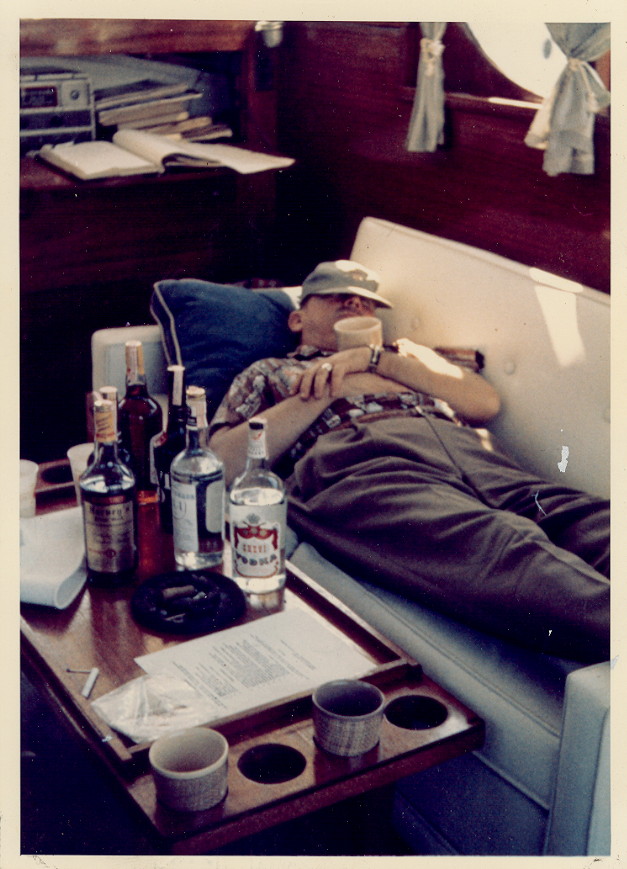

Anonymous: Enigmatic Images from Unknown Photographers by Robert Flynn Johnson

Snapshots: The Eye of the Century by Christian Skrein

Photobooth by Babbette Hines

Americans in Kodachrome 1945-1965 by Guy Stricherz

Forget Me Not: Photography and Remembrance by Geoffrey Batchen

Southern Californialand: Mid-Century Culture in Kodachrome by Charles Phoenix

other pictures - the snap*shot collection of thomas walther