View current page

...more recent posts

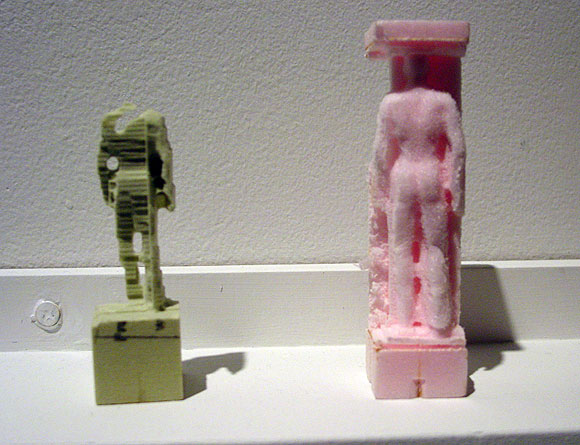

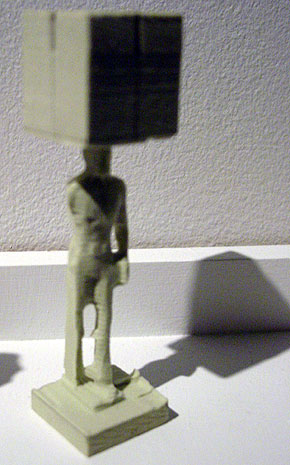

Figures by Mike Beradino at vertexList, Brooklyn, NY (show ended yesterday). An abject and rather intriguing response to Karin Sander and others working with rapid prototyping (3D printing) technology. These are made using some kind of (modified?) CNC milling, a reductive technique, but according to the gallery, extrusion (additive) techniques are also employed. Beradino puts different materials (styrofoam, wood, etc.) into the mill for computer guided laser carving, and there is also hand carving on some of the figures, I'm told. Instead of Sander's little everyman and everywoman miniatures, which relate to "life," Beradino's model is an avatar downloaded from the virtual world du jour Second Life--originally a smooth, Silver Surfer style humanoid--along with whatever artifacts and extraneous data come with the 3-D image file. Hence the cubes and frames attached to the figure and imperfect or grotesque forms. Beradino's statement suggests he takes steps to exacerbate the digital noise (see below).

(sorry about the odd sizes/focuses of my photos and the sketchiness of the info--these are rough notes and can be revised/corrected)

Karin Sander's work circa 1998 was always discussed in terms that exalted technology and the rigorousness of her process;

this text from i8 Gallery in Iceland [dead link to text removed], for example, could be from a tech start-up's prospectus:

this text from i8 Gallery in Iceland [dead link to text removed], for example, could be from a tech start-up's prospectus:Karin Sander's 1:10 is a series of three-dimensional figures that are essentially reproductions of people, fully dressed, rendered one-tenth life-size in plastic acrylic. Each figure was created by a three-step process that begins with an elaborate, 360-degree computer-driven scanning apparatus that uses up to twenty cameras to produce a 3D data file describing in minute detail the appearance, posture, and clothes of the “sitter”. After seeing the scan represent-ed as a 3D “wire model” on a computer monitor, the sitter can have the technicians redo it. The final, sitter-approved data file is then sent to another company, which uses it to produce the actual 3D figure by feeding the data into a computer-driven extruder that sprays out thin layers of plastic acrylic, each representing a horizontal cross-section of the subject's body. When the figure is finished, it is sent to an airbrush technician, who colors it according to snapshots made by technicians at the time of the original scan. Curiously, at no point in this process is Sander herself physically present. Other than accepting or (very rarely) rejecting the final product, she chooses to make no decisions concerning how the sitters will be depicted. Some subjects arrive with suitcases of clothes at the company in Kaiserslautern, Germany, that does the original scans. What they wear and how they are depicted is wholly their decision, not the artist's.Beradino seems more interested in how the tech breaks down: "My works are physical recursions, between the digital and physical. These recursions are similar to a feed back loop such as a microphone next to a speaker. The speaker output signal becomes the input of the microphone and so on and so on. An object is created then digitized then produced then digitized then produced." This introduction of random, subjective, "wild" variables into a process that's supposed to be about creating near-perfect copies is much appreciated by this viewer, as is the celebration of the do-it-yourself factor, in contrast to the oppressive '80s/early '90s art model of mediating between corporate teams as a form of social sculpture with a well crafted collectible bauble as a result. Sander's work was considered paradoxically human or humanistic for all its mediated facture. Beradino's figures also have a quality of melancholy or pathos but it is the pathos of the cyborg, and a failed one at that, a reading only implicit (or repressed) in the Sander, which for all its rigor involved a fair amount of tweaking by "professionals" to get "right."